Table of Contents

- The Catholic Church in Mid-19th Century Philadelphia

- Building the Cathedral

- Design

- Renovations

- Key Dimensions

- Artifacts and Artwork

- Side Altars, Shrines and Memorial

- Rear Mosaics

- The Chapel of Our Lady of The Blessed Sacrament

- Key Dates

- Appendices

- Self-guided tour

- Audio tour

- Photo tour

Welcome to the Cathedral

The cathedral church (Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul) is the principal church of the diocese, because it is here that the bishop as local ordinary of the diocese has his throne (chair), called the cathedra. Open since 1864 and located at the East side of Logan Square on 18th Street and the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, the cathedral is the mother church of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia. It is the largest brownstone structure in Philadelphia and the largest Catholic Church in Pennsylvania. The history of the Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul is central to the history of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia.

The Catholic Church in Mid-19th Century Philadelphia [1]

The Bill of Rights and Jefferson’s intent notwithstanding, the design and construction of the Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter & Paul in Philadelphia, was, at least in part, influenced by the virulent anti-Catholic sentiment that had erupted in that city just a few short years before the cornerstone of the Cathedral was placed. While the Baltimore Cathedral was intended as a testament to the religious tolerance upon which the new country was founded, with its large windows and open, airy, welcoming design, the Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter & Paul reflects an architectural response to extreme prejudice.

An increased influx of immigrants into the new United States at the early part of the 19th century, coupled with an economic downturn, led a faction of the population to view the predominantly working-class Irish Catholic immigrants with, at the very least, growing unease. As early as 1830, anti-Catholic publications began to appear. Mistrust and prejudice ran so high that in 1834, a mob of anti-Catholic sympathizers burned a convent in Massachusetts.

That anti-Catholic faction grew, both in number and in outspokenness, in many of the former colonies to become, in 1837, a political party known as the Native American or Nativist party. The Nativists blamed the newly arrived immigrants for the increasing problems in the urban areas, where those immigrants had largely settled. In addition, they resented the increased competition for jobs in the troubled economy. While politically the Native American party simply championed the slogan “America for Americans,” they actually sought to extend the period required for naturalization to 21 years. Their intent in doing so was to limit the voting influence of the newly arrived immigrants as well as their ability to hold public office.

When accused of being anti-Catholic and anti-Irish, members of the Native American party adamantly denied the accusation and swore that their chief object was to ensure that “church and state remain separate”. (Nativist sympathizers were sometimes called “Know-Nothings” because those aligned with the movement would claim to “know nothing” of the group’s violent or disruptive activities.) With the powder keg filled and the fuse in place, all that was needed was a match. That match ignited in 1842, when religious education within the Philadelphia public schools became an issue.

Because there were differences between the Catholic bible and the King James Version, the Bishop of Philadelphia, Francis Kenrick (1797-1863), wrote a letter to the Board of Controllers, who oversaw public education in the city, requesting that Catholic students be allowed to either use the Catholic bible or be excused from the religious classes being taught. The Board of Controllers had no opposition to this request and voted a resolution in agreement. This was interpreted in the narrow view of Nativist sympathizers as an attempt by the Catholics to dominate religious education in the public schools.

On 8 May 1844, large crowds assembled in Kensington and several skirmishes took place. As the violence escalated, Catholic homes were attacked and, ultimately, multiple Catholic structures were burned to the ground, including Saint Michael’s Church and rectory; the convent of the Sisters of Charity; and the church, rectory and library of Saint Augustine’s Church, located at 4th and Vine Streets. Several people, on both sides, were killed. Despite the presence and attempted intervention of the city troops and officials, other structures were threatened, including Saint Phillip’s. Ultimately it took the arrival of the governor and 5,000 troops to calm the riots. It was against this socio-political backdrop that Bishop Kenrick began to formulate his vision of a great cathedral in Philadelphia to provide services to the city’s growing Catholic population.

The Cathedral would be named after Saints Peter and Paul. These apostles share a feast day as founders of the church in Rome. Peter, a Galilean fisherman chosen by Christ as one of the twelve apostles, became the undisputed leader of the fledging church after Pentecost. Paul, a Pharisee and Roman citizen who had persecuted Christians, became the church’s greatest missionary, its “apostle of the gentiles.” By tradition both were martyred in Rome.

Building the Cathedral

Bishop Kenrick engaged two Vincentian priests, both of whom had studied architecture prior to joining the priesthood, to draw preliminary sketches of a proposed cathedral. When Fathers Mariano Maller, C.M. and John B. Tornatore, C.M. drew those initial sketches, the violence and anti-Catholic enmity wrought by the Know-Nothings in 1842 were still very fresh in their minds. The sketches, from which architect Napoleon LeBrun would design the building, showed the structure’s windows only at the clerestory level. There is a local legend – several versions, actually – told about the high placement of the windows. The essential story is that someone connected with the building of the Cathedral (in one version, it was the Bishop himself) had pulled aside the strongest workman he could find and had him throw stones as high as he could, and it was ordered that just above that point was where the windows were to be placed.

In 1845 a building met with financial failure and was offered for sale. The owner of the property was the Farmers’ Life and Trust Company of New York City. The property was purchased and is the present site of the Cathedral. The purchase price was $37,200. On 29 June 1846, the feast day of Saints Peter and Paul, Bishop Kenrick issued a pastoral letter soliciting funds for the construction of the Cathedral. Of particular note was the insistence by the Bishop that no work should be done without sufficient funds to pay for it. This effectively did two things: first, it ensured that the diocese would not be hampered by staggering debt during and after construction, and second, it ensured as well that construction of the Cathedral would take considerable time. The financing of such monumental and ornate structures throughout history had always been difficult and often intermittent due to lack of funds and, not incidentally, political upheaval. The Cathedral of Saints Peter & Paul would be no different. A 25-year-old local man named Napoleon LeBrun (1821-1901) was engaged as architect on the project. The cornerstone, a gift of Mr. James McClarnan was laid on Sunday afternoon 6 September 1846 at 4:30 pm at the northeast corner of the church in the presence of some 8,000 people.

Born in Philadelphia to French Catholic parents, LeBrun had apprenticed with Thomas Walter, who had built the Capitol dome in Washington, DC. Among LeBrun’s other notable local designs are The Philadelphia Academy of Music, Saint Patrick’s Roman Catholic Church on 20th Street and Saint Augustine’s on 4th Street. Eventually, LeBrun established himself in New York, along with his sons, and designed one of the earliest skyscrapers – the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company tower.

After five years of working on the Cathedral, LeBrun left the project over a disagreement with the Bishop in 1851, and John Notman (1810-1865) assumed the responsibility of the Cathedral’s completion. Notman, a well-respected architect, is most famous for his work in the Gothic Revival style, particularly for his design of Saint Mark’s Episcopal Church on Locust Street in Philadelphia, the Chapel of the Holy Innocents in Burlington, NJ, and the Episcopal Church of the Holy Trinity on Rittenhouse Square. Notman left the Cathedral project in 1857 over a dispute regarding his fees. A third architect, John Mahoney, apparently managed the construction until LeBrun returned sometime around 1860.

The leadership of the Philadelphia diocese changed three times over the course of construction. In 1851, Bishop Kenrick was elevated to the office of Archbishop of Baltimore, just 5 years after the cornerstone was laid. Father John Neumann (1811-1860) succeeded him as Bishop of Philadelphia in 1852 and continued the work on the Cathedral. In 1857, Bishop James Wood (1813-1883) became coadjutor Bishop of Philadelphia and would replace Bishop Neumann upon his death in 1860. Bishop Wood was trained in business and banking and was at once given the task of completing the Cathedral. As a temporary measure in 1857, Bishop Wood had a small chapel built on Summer Street for the convenience of parishioners who had been attending services in the chapel of the Bishop’s home. By September of 1859, the walls of the Cathedral were completed, and on 14 September 1859, with Bishop Neumann presiding, the keystone was placed and the cross was raised to the top of the dome by Bishop Wood. Bishop Martin Spaulding of Louisville gave the address. Four months later Bishop Neumann died.

Bishop Wood noted the costs incurred by having construction stop when funds weren’t available and allowed the church to borrow money for its continuation – in direct contrast to the original intent of Bishop Kenrick. Yet, despite the issue of funding, the management of construction, and the interference wrought by the onset of the Civil War, Bishop Wood completed the Cathedral and presided over its dedication on 20 November 1864. The Cathedral was formally consecrated in 1890.

Design

Although it might be tempting to conclude that the Neo-Classical design of the Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter & Paul was solely a response to the anti-Catholic violence, Bishop Kenrick, in a letter to his brother the Bishop of St. Louis, clearly expressed that he did not care for Gothic architecture and that a cathedral in Philadelphia would not be of that design. It seems that the Cathedral of Saints Peter & Paul was, from the outset, intended to be of Neo-Classical design, with that architectural style’s barrel arches, Corinthian columns, and triangular pediments supported by columns at the entrances. Yet the placement of the windows at only the clerestory level is in strong contrast to the Baltimore Cathedral – also of Neo-Classical design – and most likely the result of concern over potential anti-Catholic violence.

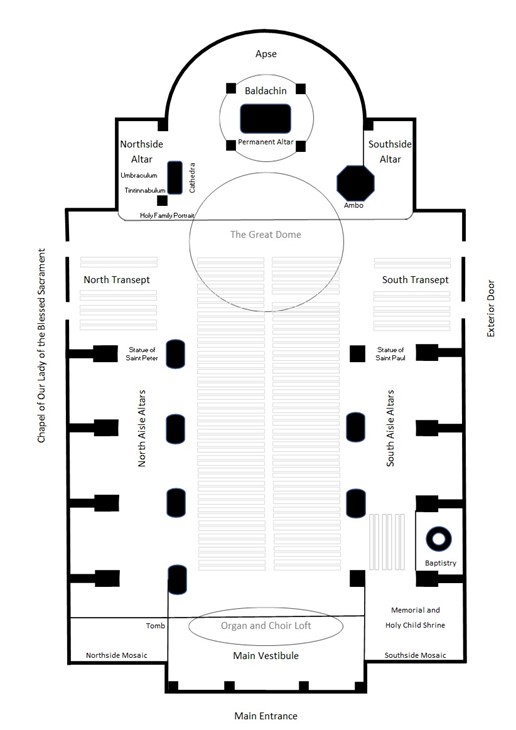

LeBrun’s design for the Cathedral was modeled after the Lombard Church of Saint Charles (San Carlo al Corso) in Rome in the Neo-Classical style of the Italian Renaissance. Like so many churches and cathedrals in Europe, it would have a cruciform floorplan. It was constructed of Connecticut and New Jersey brownstone and is topped by a great copper dome which has acquired a green patina. Though never built, a bell tower was envisioned for the northeast corner and there were several other modifications to the original design over the course of construction. The gilded surfaces and detailed sculptural elements, along with the choice of rich finishes of marble and walnut, give this relatively young cathedral a distinct sense of timelessness. The interior decorations are largely the work of Constantino Brumidi (1805-1880). Brumidi also painted the Capitol in Washington, DC.

Renovations

The venerable edifice was completely renovated in 1914 under the direction of Archbishop Edmond F. Prendergast (1843-1918). The interior walls were painted and the works of art were rearranged or replaced to be more effective with the new high altar of white marble. New confessionals were added and a complete renovation of the crypt was completed. The weathered tin roof was recovered with copper and the dome refurbished with the same material.

On the Feast of the Maternity of Our Lady, 11 October 1955, The Chapel of Our Lady of the Blessed Sacrament, newly-built on the north side of the Basilica, was dedicated. lt replaced the old chapel that was built in 1856. Completion of the chapel made it possible to close the Cathedral for renovations. From 1956 to 1957, shortly after the chapel was completed, major renovations to the Cathedral were carried out. This project was at the direction of John Cardinal O’Hara (1888-1960) and involved the structure of the building.

The principal work of the 1956-57 renovation was the construction of the semi-circular apse to provide a spacious area for the main altar. Most notable is that windows were placed at ground level in the enlarged apse behind the altar during this renovation.

Key Dimensions in the Cathedral Basilica

- Foundation walls from 5 to 10 feet thick

- Walls of the building are 4 feet 6 inches thick

- The structure measures approximately 300 feet in length, 136 feet in width, and 101 feet 6 inches in height from the pavement to the apex of the pediment

- The dome rises over 60 feet, is 71 feet in diameter at the base, and rises 156 feet 8 inches above the floor of the Cathedral

- The total height of the Cathedral is 209 feet to the top of the 11-foot gold cross

- The ball under the gold cross is 6 feet 8 inches in diameter

- The current sanctuary is 91 feet deep

- The great nave is 50 feet wide and 236 feet long

- The vaulted ceiling is 80 feet above the floor

- The canopy over the altar is 38 feet high

- The walnut pews seat over 1,000 people, with capacity for almost 1500 by the use of temporary chairs.

- The confessionals are walnut-stained oak; their privacy is secured by red velvet curtains.

- Six Verte lmperial marble columns, rising 40 feet high and weighing in excess of twenty-five tons each, are set into the curved wall of the apse.

- The canopy or baldachin over the altar is of antique Italian marble. lt stands 38 feet high and is surmounted by a semi-circular dome of bronze panels.

- The floor is of white and dark green marble tiles over an inch thick. A white marble altar rail with three bronze gates separates the nave and transept from the sanctuary.

- The facade of the Cathedral is graced by four massive stone columns of the Corinthian order, over 60 feet high and 6 feet in diameter.

Artifacts and Artwork

The interior of the Cathedral Basilica includes a beautiful collection of artifacts and artwork.

The Sanctuary – The principal work of the 1956-1957 renovation was the construction of the semi-circular apse to extend the sanctuary. The focal point is the permanent altar, which faces east. It is constructed of Botticino marble with Mandorlato rose marble trim. Three bronze discs decorate the front, the central one of which bears the Greek inscription of Jesus Christ, IHS.

The baldachin (canopy) over the altar is of antique Italian marble. The underside of the dome is a marble mosaic. Its central figure is the dove, symbol of the Holy Spirit. The mosaic carries the Latin inscription “In omni loco sacrificatur et offertur nomini meo oblatio mundo.” (“In every place there is offered and sacrificed in My Name a clean oblation.” (Malachi 1:11)) The capitals are cast bronze and angels of white Italian marble stand 10 feet high at the corners of the baldachin. The decorative rosettes are of Botticino marble.

Six giant Verte Imperial marble columns are set into the curved wall of the apse. Interspersed between these pillars at the rear of the sanctuary, are stained-glass windows by Connick of Boston. The center window, devoted to the Eucharist, depicts the sacrifice of Melchizedek, the multiplication of the loaves and fishes, and the Last Supper. The window to the left portrays three events in the life of Saint Peter: his call by Christ to be a fisher of men, Christ giving Peter the keys to heaven as Prince of the Apostles (one key represents temporal power and the other represents spiritual power), and his crucifixion upside-down since he considered himself not worthy to be crucified as Jesus Christ was crucified. The window to the right reveals three scenes from the life of Saint Paul: his conversion on the road to Damascus, his preaching to the Athenians about the unknown God, and his death in Rome by beheading. Between the stained-glass windows are two mosaics in Italian marble. One shows Saint Peter with Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome as the background, and the other represents Saint Paul with Saint Paul’s Basilica Outside-the-Walls of Rome in the background.

The inscription behind the main altar in the sanctuary reads “Tu es Petrus et super hanc petram aedificabo Ecclesiam meam” (“Thou are Peter and upon this rock I will build my Church” (Matthew 16:18)).

In 2007, the tabernacle was moved to the main altar. Saint Jude Liturgical Arts Studio designed, fabricated, and built the Blessed Sacrament tabernacle which is located under the existing baldachin. The materials that make up the tabernacle match materials used elsewhere in the Cathedral. The tabernacle door and the columns to the left and right of the door imitate the Cathedral’s interior architecture. Inside the tabernacle door is a silver medallion of the resurrected Christ. The sanctuary lamp (on the left) which burns continuously is a reminder that this tabernacle is the place that reserves the Blessed Sacrament in the Cathedral. The crucifix and candlesticks are bronze.

The Great Dome – The great dome rises 156 feet 8 inches above the floor of the Cathedral. The interior reveals a striking 1862 painting, The Assumption of the Blessed Virgin by Constantino Brumidi. At the next level are panel paintings entitled Angels of the Passion. With each group of angels is an emblem of the passion. In clockwise order (facing the main altar) they are the chalice (Blood of Christ), the cross, the crown of thorns, Veronica’s veil, angels weeping, stripping of garments and scepter, the host (Body of Christ), angels weeping, the nails, the banner reading INRI, the sponge on a reed, and the scourging pillar.

On the third level, the stained-glass windows show Mary holding the Child Jesus, with Saint Peter on her right and Saint Paul on her left. The remaining windows are all Doctors of the Church. In clockwise order (facing the main altar) the windows depict Saint Paul, Saint Augustine, Saint Jerome, Saint Ambrose, Saint Gregory, Saint Leo, Saint Basil, Saint John Chrysostom, Saint Cyril, and Saint Athanasius.

The medallions on the spandrels at the base of the dome represent the four evangelists, Saints Matthew (angel), Mark (lion), Luke (winged ox), and John (eagle).

The Cathedra and Choir Stalls – The choir stalls, the hand-carved wooden screens which separate the sanctuary from the side altars, and the Cardinal-Archbishop’s cathedra, throne, or chair are of American black walnut. On the wall under the canopy of the throne is the coat of arms of the head of the Archdiocese. The wooden screens were inspired by the famous metal rejeria of the Spanish Renaissance found in many cathedrals in Spain.

High above the choir stalls on each side of the sanctuary are stained-glass windows. The window on the throne side bears the coat of arms of Pope Benedict XV (1854-1922); that on the ambo side, the insignia of Archbishop Prendergast. These remain from 1914, a reminder that it was during the papacy of the former and the episcopacy of the latter that the first extensive renovations of the Cathedral were carried out. Archbishop Prendergast’s coat of arms carries his motto “Ut Sim Fidelis” (“May I be faithful”).

Umbraculum and Tintinnabulum – One of the two symbols used to indicate that a church has the dignity of a Basilica is the umbraculum (Italian: ombrellino, “little umbrella”). It is a historic piece of the papal regalia and insignia, once used on a daily basis to provide shade for the pope. The cloth is red and gold velvet. It was placed in the sanctuary of the Cathedral in 2011. The second is the tintinnabulum, a bell mounted on a pole. In December 2013, the tintinnabulum, the papal tiara and the Keys of Heaven on the top, were placed in the Basilica to signify our link with the pope. If a pope was to say mass at the Basilica, the tintinnabulum would be used to lead the very special procession down the aisle. In 1976, Monsignor James Howard (1925-2014), petitioned Rome to designate the Cathedral as a minor Basilica. Pope Paul VI (1897-1978) raised the Cathedral to the dignity and honor of minor basilica, in time for the canonization of Bishop Neumann in 1977. This honor was bestowed after the Archdiocese of Philadelphia hosted the 41st International Eucharistic Congress. Among the attendees and speakers was Mother Teresa of Calcutta, now Saint Teresa.

The Holy Family Portrait – This painting is by Neilson Carlin, who is from Kennett Square in Pennsylvania. It portrays the Holy Family, Jesus, Mary, Joseph, Ann and Joachim. Notice the white semicircular top of the painting, it matches the top of the Basilica’s baldachin. Notice the same Corinthian arches on the altar and in the painting. This portrait was the official image for the September 2015 World Meeting of Families.

Ambo – The ambo, opposite the Archbishop’s throne, is octagonal in shape. lt is constructed of imported marble matching the altar and has a carved walnut canopy. On the front, we see the Greek letters alpha/omega, (beginning and end). The Holy Spirit is found on the back wall and is represented by the dove and the rays represent the seven gifts of Holy Spirit.

Side Altars – The side altars of the sanctuary are the design of the original architect, Napoleon LeBrun. They were placed in 1887 and dedicated to the Sacred Heart of Jesus (south side) and to the Blessed Virgin Mary (north side). Above the altars are the famous Venetian glass mosaics of The Apparition of Our Lord to Saint Margaret Mary Alacoque (south side) and The Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary (north side). These were executed in 1915 in Venice, Italy but due to World War I, shipment to the United States was delayed and they were installed in the Cathedral in 1918.

Transept Paintings and Stained Glass – Over the transepts are paintings which remain from the earlier renovation (1915) of the Cathedral: Filippo Costaggini’s The Ascension of Our Lord (northside transept) and Arthur Thomas’ The Adoration of the Magi (southside transept). The latter was re-painted by Moricz L. Tallos in 1980. Each is approximately 16 by 25 feet. The north transept includes a stained-glass window of the resurrection of our Lord; the window in the south transept shows the visit of the shepherds to the infant Jesus in the nativity. The doors on either side of the north transept mural lead into The Chapel of Our Lady of the Blessed Sacrament.

Statues of Saint Peter and Saint Paul were placed in the Cathedral Basilica in August 2009. They were moved from the Church of the Most Blessed Sacrament, now closed, in Philadelphia. Saint Peter is depicted holding the keys to the kingdom, representing the heavenly and temporal authority bestowed upon Peter by Christ. The book carried by Saint Paul represents his epistles in the New Testament of the Bible. The sword is a reminder of the means of his martyrdom – he was beheaded in Rome in 67 AD.

Stations of the Cross – Stations of the Cross were crafted at the Sibbel Studio, the same studio that designed the Immaculate Conception statue in front of the Cathedral. The Stations are from Saint Boniface Church and are made of cast iron. They were cleaned and placed at the Cathedral Basilica in 2008. They were sculpted by John Sibbel in 1910 at a cost of $100 each.

Clerestory Windows, Ceiling, and Lighting – Natural light is admitted through the clerestory windows close to the ceiling. These are of lightly tinted glass and carry simple religious symbols (IHS (Christ), three lilies representing the Trinity, a key (Saint Peter), a cross, a crown of thorns, a sword and scripture (Saint Paul)) as their most prominent decorations. Gold rosettes on a rich blue background adorn the coffered ceiling. Bronze chandeliers, weighing a half ton each, light the nave.

Burial Crypt – The burial crypt (not open to the public) under the main altar of the Cathedral is the final resting place of the remains of most of the ordinaries of the Archdiocese as well as other bishops and clergymen of Philadelphia. The crypt can be reached through both the sanctuary and by way of an ambulatory that extends from the rectory to the sacristy on the exterior apse wall. The walls and the ceiling of the crypt are of white Carrara marble. Within the crypt is a simple altar of Carrara marble where mass is celebrated for the deceased.

A common practice in important cathedrals and churches is the interment of those either important to the faith in general or those integral to that location. The Cathedral Basilica is no different. The remains of Bishop Conwell and Bishop Egan, the first two bishops of Philadelphia, were the first to be transferred to the crypt in 1869. In vaults of the crypt also lie the remains of Cardinal Joseph Dougherty (1st Cardinal Archbishop of Philadelphia) and Cardinal Anthony Bevilacqua.

Choir Loft – The choir loft is at the rear upper level of the Cathedral. The organ screen, constructed of carved walnut, is so arranged as to open on a view of the majestic stained-glass window of the Crucifixion of Jesus over the main entrance of the Cathedral Basilica. The richly ornamental screen is the design of Otto Eggers, who is also responsible for the designs of the Jefferson Monument, the Mellon Art Gallery, and the National Gallery of Art, all in Washington, D.C. The casing which encloses the pipes is one of the most outstanding in the country. lt has been cited in national organ periodicals and organ-building manuals. The case enclosing the organ was most likely built by Edwin Forest Durang (1829-1911), one of the Cathedral architects and builders.

Organ – The Cathedral organ is one of the largest in the city of Philadelphia, having seventy-five ranks of pipes, ninety stops and 4,648 pipes on four manuals and pedals. The Cathedral’s first organ was built by John C.B. Standbridge in 1869 at a cost of $10,000. It was replaced by a new instrument in 1920 at a cost of $30,000. The new instrument, Opus 939, was built by the Austin Organ Company of Hartford, Connecticut. In the 1957 renovations a new console was installed and the organ was rebuilt by the Tellers Organ Company. During these renovations, the organ loft was expanded to provide more room for the choir. The choir was established in the 1920’s. During 1975-76, major renovations were completed on the organ in preparation for the 41st International Eucharistic Congress and the United States Bicentennial. In 1977 the Tellers console was replaced with a used Austin Console, originally built in 1922 for the Rochester Theatre. Further restoration undertaken in 1987 included the addition of the Trumpet en-chamade, situated on the ceiling of the organ case. A chancel organ of 11 ranks, built in the 1950s by the M.P. Moller Company, was also installed. An echo organ is situated in the sanctuary. The organ is considered perfectly placed, speaking directly into the nave. The inscription in Latin in the vaulted ceiling above the organ reads “Vas electionis est mihi iste, ut portet nomen meum coram gentibus.” (“He [Saint Paul] is a chosen instrument of mine to carry my name before the Gentiles.” (Acts 9:15))

Exterior Statues – The four statues in the niches, empty until 1915, include: The Sacred Heart, to whom the diocese was consecrated by Bishop Wood on 15 October 1873; Mary, the lmmaculate Conception, proclaimed patroness of the United States at the First Council of Baltimore in 1846; and Saints Peter and Paul, dauntless defenders of the faith and patrons of the Cathedral Basilica. The statue of Mary, the lmmaculate Conception was placed in the niche in 1918. It was sculpted at the Joseph Sibbel Studios. The Statues of Saints Peter and Paul were sculpted in the Gorham Studios. The statues of Saint Peter and Paul were moved from the Church of the Most Blessed Sacrament (now closed) in Philadelphia.

Doors – Cast bronze doors and hand railings leading from the main facade into the narthex or vestibule, were added in 1957. The front doors face west. The handrails, along with the doors of the Race Street entrance to the Cathedral, are also of bronze. Exterior lighting makes it possible for the impressive facade of the Cathedral to be seen at night and especially enjoyed by pedestrians and motorist on the Parkway or Logan Square.

Bell – The bell located in the cupola on the roof above the main altar was made by the Meneely Bell Foundry in West Troy, New York in 1874 and is inscribed with the words “Ave Maria Immaculata” (“Hail, Mary Immaculate”).

Side Altars, Shrines and Memorial

There are eight side altars in the Cathedral proper:

The first on the south aisle is the altar to the Blessed Virgin Mary. An altar to the Eucharist was removed in 2008 to install the new, more classical altar to the Blessed Virgin Mary under the title of Our Lady of Grace/Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal. The altar to Our Lady of Grace is new to the Cathedral but was formerly located in North Philadelphia’s Saint Boniface Church and dates from 1868. The statue of the Blessed Mother is a rendition of the image on the Miraculous Medal. The medallion above the statue of the Blessed Mother as Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal originated with Mary herself. The medal is based on two apparitions of the Blessed Virgin to Saint Catherine Labouré in 1830.

On the front of the medal, the Blessed Virgin stands on a half-globe, her foot crushing the head of the serpent. Her arms are outstretched, with rays issuing from her extended hands, the symbol of the graces which she obtains for those who ask for them. Surrounding this image is the invocation, “O Mary conceived without sin, pray for us who have recourse to thee!” The reverse side of the medal (the medallion above the statue) bears a cross with a bar at its foot that is intertwined with the letter “M”. Beneath the letter are the hearts of Jesus and Mary, both surmounted by flames of love, one having a crown of thorns and the other pierced with a sword. Encircling all of this are 12 stars around the oval frame.

The icon of Our Lady of Perpetual Help is a copy of a 15th-century original painted in Byzantine style. It was enthroned in the Cathedral Basilica by Cardinal Rigali in 2009. The original has been in the custody of the Redemptorist Fathers (Saint John Neumann was a Redemptorist) in Rome’s Saint Alphonsus Church since the 19th century. The reproduction, which was donated by the Redemptorists, is a copy originally obtained from the Vatican and had a place at Saint Boniface Church. Our Lady of Perpetual Help is the patroness of the Redemptorists. In addition to using the altar from Saint Boniface Church, the altar to the Blessed Virgin is enclosed by sections of the original marble altar rail from Saint Boniface Church.

The second altar on the south aisle is dedicated to the Purgatorial or Holy Souls. The altar is a copy of the grand altar of The Chapel of the Most Blessed Sacrament in Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome, which is considered one of the most beautiful altars in the Eternal City. It was designed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680). The focal center of the altar is the Ciborium. Two angels kneel at the sides, a motif dear to Bernini from the beginning of his career. These two figures are magnificent and at the same time light because of the wide looseness of their robes, the affected grace of their attitudes and the expressive ecstasy of their faces. The columns that support the dome are of the finest Paonazzo marble, streaked with dark veins. The top table of the altar, where the angel figures and tabernacle rest, is engraved with “Requiem Aeternam Dona Eis Domine” (“Eternal Rest Grant Unto Them O Lord”). The next layer of the altar, slightly recessed and all white, is a domed edifice with three pillars on each side. Three smaller angels are among the pillars. The ones on each side have hands crossed over chest and the one in the middle is with hands together in prayer. The dome is topped with the Holy Spirit (a dove figure) in the middle. Sitting at the very top is a brass cross. The altar was erected in 1906 and is a gift of Mr. William J. Power, who for more than half a century was associated with the business offices of the diocese.

The third altar on the south aisle was enlarged in 1956 to a semi-circular apse for the Baptistry. The apse was added with an exquisite stained-glass window, from Connick of Boston, depicting the baptism of Jesus by Saint John the Baptist and Saints Peter and Paul baptizing prisoners in the Mamertine prison in Rome with water from a miraculous spring. The Mandorlato Rose baptismal font is surmounted by a bronze dome with the inscription of the Sign of the Cross, “In nomine Patris et Filii et Spiritus Sancti, Amen” (In the name of the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Spirit, Amen”). The baptistry is enclosed by a bronze screen inspired by a similar one in the Cathedral of Toledo in Spain. Set into the top center of the screen is the coat of arms of Cardinal O’Hara, carrying his motto in Latin “Ipsam Sequens Non Devias” (“lf you follow her you shall not go astray”, referring to our Lady).

The fourth altar on the south aisle is the altar dedicated to Saint John Neumann in 2009. New to the altar is the imposing seven-foot marble statue sculpted at Saint Jude Liturgical Arts Studio in Italy. Saint John Neumann (1811-1860) was born in what is now the Czech Republic, studied in Prague, came to New York at the age of 25 and was ordained a priest. He did missionary work in New York and at 29 joined the Redemptorists and became its first member to profess vows in the United States. ln 1852 Saint John Neumann became the fourth Bishop of Philadelphia. While Bishop of Philadelphia, he founded the first Catholic diocesan school system in the United States and drew into the city many teaching communities of sisters and the Christian Brothers. On 13 October 1963, John Neumann became the first American Bishop to be beatified. Canonized in 1977, he is buried in Saint Peter the Apostle Church at 5th and Girard Streets in Philadelphia, at his request. He is the first male American citizen to be canonized.

Venerable Cornelia Connelly Memorial and Holy Child Shrine – Cornelia Connelly, SHCJ was a wife, mother, and convert to Catholicism. She was an American-born educator who was the foundress of the Society of the Holy Child Jesus, a Catholic religious order. Venerable Cornelia Connelly has been proposed for sainthood in the Catholic Church. The Holy Child Shrine is an image that can be found in most American Holy Child Schools and convents.

The first altar on the north aisle is dedicated to Saint Joseph and was blessed by Cardinal Rigali on 6 June 2009. This altar has a sculpted seven-foot marble statue of the honored saint over its altar and a marble reredos which serves as backdrop. Although new to the Cathedral Basilica, the altar formerly graced North Philadelphia’s Saint Boniface Church from 1866 through 2006 and dates from the late 19th century. The altar is enclosed by sections of the original marble altar rail from Saint Boniface Church.

The second altar on the north aisle is the altar to Our Lady of Guadalupe. This altar was originally the Saint Joseph altar and afterwards rededicated to the Holy Family during the 1956-1957 renovations. lt contained an original oil painting of the Holy Family. The original altar table remains as part of the altar to Our Lady of Guadalupe. The Lamb reclining on the cross on the front of the altar table is a symbol of the Eucharist.

The altar of Our Lady of Guadalupe was the thought of Cardinal Rigali. He promised Our Lady and the Hispanic community to have the image of Our Lady, who is the Patron of the Americas and Our Lady of the Unborn, installed in the Cathedral Basilica. His Eminence approached the craftsmen at the Studios of Saint Jude Liturgical Arts to design and build the altar in Her honor. After much thought and consideration, it was believed that the altar which previously had the Holy Family Triptych would be a perfect setting for the new altar. It was installed in the Cathedral Basilica in December 2009.

The Studios of Saint Jude Liturgical Arts in Philadelphia, prepared drawings and designs incorporating the old altar. This altar was made of Vermont marble and is no longer quarried. Unlike the other altars which have statues of saints and Our Lady of Grace (Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal), the best way to depict the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe and her image on Juan Diego’s tilma would be a mosaic. The altar was then designed to complement the architecture of the Cathedral Basilica and the other altars. Actual authenticated images of Our Lady of Guadalupe were obtained from Mexico. Thousands of tesserae (small glass squares) were used to create the image. The smaller the tessera, the more intricate and detailed the image. Some of these glass tiles were so small they were installed using tweezers. Each piece of glass was hand placed in the old tradition of the Venetian mosaics done thousands of years before. 24 karat gold leaf Venetian glass was used throughout the garments and starburst around Our Lady. The mosaic took two men more than four months to create. After the mosaic was complete, a marble altar to surround and frame the mosaic was created. Over 11 tons of marble were used to create the altar and medallion. The individually carved roses that surround the frame of the mosaic were designed to mirror the roses that Saint Juan Diego delivered to the Bishop when he unveiled the image of Our Lady on his tilma.

The third altar on the north aisle is the memorial altar to Archbishop Patrick John Ryan (1831-1911), the 6th Bishop of the Cathedral Basilica. Designed in the ancient Celtic-Romanesque style of architecture, it is remarkable for its nine-foot sculptured Celtic cross. One interpretation of the Celtic Cross claims that placing the cross on top of the circle represents Christ’s supremacy over the pagan symbol of the sun. To the left of the cross is a statue of Saint Patrick and to the right a statue of Saint John the Evangelist, Archbishop Ryan’s patron saints. Saint Patrick is seen on the left with a shamrock in his hand, the symbol he used to teach the Irish about the Blessed Trinity. On the right is a statue of Saint John the Evangelist standing next to his symbol, the eagle. lt is no coincidence that the side altar honoring Archbishop Ryan and that honoring Saint Katharine Drexel are placed next to each other. Archbishop Ryan officiated when Sister Katharine Drexel took her final vows. Archbishop Ryan also officiated at the wedding of Mother Katharine Drexel’s sisters. Mr. Francis Drexel, Saint Katharine Drexel’s father, was an advisor to Archbishop Ryan.

The fourth altar on the north aisle is the Shrine to Saint Katharine Drexel dedicated in 2009 and was especially challenging to complete because the marble statue had to be based on the true likeness of Saint Katharine. lt was especially important that the original altar be retained at the Saint Katharine Shrine because it was donated in the 19th century by Saint Katharine herself, along with her sisters Elizabeth and Louise, as a memorial to their deceased parents, Francis and Emma Drexel. The sacred remains of Saint Katharine Drexel were translated to the Cathedral Basilica on 2 August 2018. The new tomb was solemnly installed on 18 November 2018.

Rear Mosaics

John Cardinal Krol (1910-1996) made a number of changes and additions to the Cathedral Basilica and The Chapel of Our Lady of the Blessed Sacrament, which enhance their beauty and increase their effectiveness for solemn celebrations. ln the summer of 1975, to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Philadelphia as an archdiocese, two mosaic murals designed by Leandro Velasco (1933- ) of Rambusch studios and executed in Venice, were set in place. The murals were inspired by the generosity of Cardinal Krol and Mr. John McShain.

The north mosaic mural depicts people and events in the Church’s involvement with Pennsylvania history. At the top are the coats of arms of Pope Paul Vl and John Cardinal Krol, and at the bottom is the symbol of the 41st Eucharistic Congress celebrated in Philadelphia in 1976. The historic scenes are of George Washington and members of the Continental Congress at Old Saint Mary’s Church; at the time Mother Katharine Drexel, but now Saint Katharine Drexel, foundress of the Blessed Sacrament Sisters; Sisters of Saint Joseph caring for the wounded on the Gettysburg battlefield; and Commodore Barry, founder of the United States Navy. The representation of Saint Charles Seminary, founded by Bishop Kenrick in 1832, includes a silhouette of the artist, Thomas Eakins, on a bicycle. The other buildings are Saint Michael’s and Saint Augustine’s churches, burned and rebuilt during the “Know-Nothing” riots and Saint Martin’s Chapel at Saint Charles Seminary. Saint Mary’s Church was the first Cathedral of Philadelphia and it was the site of the first public religious commemoration of Independence Day on 4 July 1779.

The south mosaic mural is dedicated to the life and works of Saint John Neumann, fourth Bishop of Philadelphia, who is the central figure in his episcopal garments. The phrase by which he shaped his life “Soli Deo” (“For God alone”), is repeated in German and Italian. The Cathedral at the top recalls the Bishop’s joy at the completion of its exterior in 1859. ln further scenes Bishop Neumann is present at the promulgation of the dogma of the lmmaculate Conception in 1854 at Pope Pius lX’s invitation. Also shown are the symbols of the eighty churches built during his years in Philadelphia (Saint Peter’s Church, where the Bishop is buried, is recognizable) and he is surrounded by members of the numerous religious communities which he introduced to the diocese. ln a scene suggestive of his zeal in traveling in the most remote areas to confer Confirmation, the Bishop receives young people and their sponsors. The monstrance recalls Bishop Neumann introducing into the diocese the tradition of the Forty Hours Devotion in 1853, an annual three-day period of Eucharistic adoration, and the rule he wrote for the confraternity of the Blessed Sacrament.

The Chapel of Our Lady of The Blessed Sacrament

The Chapel of Our Lady of the Blessed Sacrament, on the north of the Cathedral, can be entered from the Cathedral proper or from The Chapel’s main entrance on 18th Street. It is better known as either The Chapel or The Blessed Sacrament Chapel. The Chapel was planned as a memorial of the Marian Year and was dedicated on the Feast of the Maternity of Our Lady in 1955. The completion of The Chapel made it possible to close the Cathedral for renovations in 1956-1957. John McShain, Inc., of Philadelphia was the builder and Eggers and Higgins, Inc., of New York City were the architects.

The Chapel is Roman Classic architecture; the façade is dressed brownstone. The interior is noted for its simplicity. The altar is of Verde Antique marble. The reredos was replaced with marble in 2009 by Cardinal Justin Rigali. The tester or canopy is of matched grain walnut with hand-carved filigree, finished with gilt. The stained-glass window over the side entrance is Mary Queen of the Universe. The remaining side windows picture the Seven Joys of Our Lady: The Annunciation, The Visitation, The Nativity, The Adoration of the Magi, Jesus in the Temple, The Resurrection, and The Assumption. The circular window over the main entrance shows the Blessed Mother looking down on the Blessed Sacrament in a monstrance.

Key Dates

1837 – The diocese was consecrated to the Sacred Heart by Bishop Wood in 1837.

September 6, 1846 – Cornerstone laid by Bishop Kenrick; Napoleon LeBrun, Architect.

1852-1860 – Bishop John Nepomucene Neumann, C.Ss.R., (Saint John Neumann) Bishop of Philadelphia. Cathedral building continued.

1857 – Bishop James Frederick Wood assigned as Coadjutor Bishop and assigned by Bishop Neumann to complete the Cathedral.

1862 – Major frescoes and paintings completed by Constantino Brumidi, known as the “Michelangelo of the United States Capitol”.

June 29, 1864 – Cathedral Parish founded.

November 20, 1864 – Completed Cathedral dedicated by Bishop Wood; first Mass in the Cathedral.

1875 – Diocese becomes an Archdiocese. Bishop Wood becomes first Archbishop of Philadelphia.

June 29, 1890 – Cathedral consecrated by Archbishop Patrick John Ryan

1913-1917 – Cathedral renovated. Oak confessionals, new murals in transepts, cooper replaces tin on dome, stained glass in upper windows, sanctuary and nave.

1954 – The Chapel of Our Lady of the Blessed Sacrament replaces the old Cathedral chapel.

1956-1957 – Renovation of the Cathedral. Addition of the semi-circular apse to extend the sanctuary; new main altar, ambo, baptistery, choir loft, organ screen and organ, American black walnut pews and woodwork, bronze chandeliers, lighting, bronze front doors, and first lower stained-glass windows.

June 24, 1971 – Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

August 1-8, 1976 – 41st International Eucharistic Congress is held in Philadelphia.

September 9, 1976 – Pope Paul VI designates the Cathedral a minor basilica.

October 3, 1979 – Pope John Paul II (1920-2005) visits Philadelphia and the Cathedral Basilica.

2012 – The Cathedral received the Preservation Achievement Award from the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia in recognition of the Cathedral’s most recent exterior renovations.

September 2015 – Pope Francis visits and celebrates mass at the Cathedral Basilica as part of the World Meeting of Families.

Appendices

Our Lady of Guadalupe

Juan Diego, a 57-year old Aztec Indian convert lived in a village a few miles north of the present Mexico City. On Saturday, 9 December 1531, Juan Diego experienced his first vision of the Virgin Mary. While on his way to Mass, he was visited by Mary, who was surrounded in heavenly light, on Tepeyac Hill on the outskirts of what is now Mexico City. She spoke to him in his native language and asked him to tell the Bishop to build a shrine to her on the hill. The Bishop did not believe Juan Diego’s story and asked for proof that Mary had appeared to him. On 12 December, while searching for a priest to administer last rites to his uncle, Juan Diego was visited by Mary again. He told her of the Bishop’s answer, and she instructed him to gather roses and take them to the Bishop as a sign. She also informed Juan Diego that his uncle would recover from his illness. Juan Diego found many roses on the hill even though it was winter. When he opened his tilma (cloak) while appearing before the Bishop, dozens of roses fell out, and an image of Mary, imprinted on the inside of his cloak, became visible. Having received his proof, the Bishop ordered that a church be built on Tepeyac Hill in honor of the Virgin. Juan Diego returned home and found his uncle’s health restored.

For the rest of his life Juan Diego lived in a hut next to the church built in honor of Mary and took care of the pilgrims who came to the shrine. He was buried in the church, and his tilma can still be seen in the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe. His existence, which had been questioned by Catholics and non-Catholics alike, was confirmed by the Vatican, and Juan Diego was beatified on 6 May 1990, and canonized on 31 July 2002, by Pope John Paul II. Numerous miracles have been attributed to him, and he remains one of the most popular and important saints in Mexico.

Saint Katharine Drexel

Katharine Drexel was born in Philadelphia on 26 November 1858, the second child of Hannah and Francis Anthony Drexel. Hannah died five weeks after her baby’s birth. For two years Katharine and her sister Elizabeth were cared for by their aunt and uncle, Ellen and Anthony Drexel. When Francis married Emma Bouvier in 1860, he brought his two daughters home. A third daughter Louise was born in 1863. The children grew up in a loving family atmosphere permeated by deep faith. The girls were educated at home by tutors. They had the added advantage of touring parts of the United States and Europe with their parents.

By word and example Emma and Francis taught their daughters that wealth was meant to be shared with those in need. Three afternoons a week Emma opened the doors of their home to serve the needs of the poor. When the girls were old enough, they assisted their mother. When Francis purchased a summer home in Torresdale, Pennsylvania, Katharine and Elizabeth taught Sunday school classes for the children of employees and neighbors. The local pastor, Reverend James O’Connor (1823-1890; later became Bishop of Omaha) became a family friend and Katharine’s spiritual director.

When Katharine was twenty-one, her mother was diagnosed with cancer. Katharine nursed her through three years of intense suffering. During this time, she frequently thought that Christ might be calling her to the religious life. After Emma’s death, Katharine wrote to Bishop O’Connor about it. He advised her to “think, pray and wait.”

Francis Drexel died suddenly in 1885. According to his will, during their lifetimes the three sisters inherited the income from his estate, but not the principal. The principal would go to their children, but if no children survived them, the money was to be distributed to the charities he listed. Monsignor Joseph Stephan, director of the Catholic Bureau of Indian Missions, introduced Katharine and her sisters to the plight of the Native Americans. Travelling with him and with Bishop O’Connor, the young women visited several remote reservations in 1887 and 1888. They met with tribal leaders and witnessed the dire poverty endured by the people. Katharine began building schools on the reservations, providing food, clothing and financial support. Also aware of the suffering of the black people, she extended her love to them. During her lifetime, through the Bureau of Colored and Indian Missions, she supported churches and schools throughout the United States and abroad.

In 1889 Bishop O’Connor agreed Katharine was called to be a religious, but despite her preference for a cloistered life he urged her to found a congregation to work with the Black and Indian peoples. She hesitated, but after taking it to prayer she accepted this as her vocation. She pronounced her vows as the first Sister of the Blessed Sacrament on 12 February 1891. She and thirteen companions moved into Saint Elizabeth Convent in Bensalem in 1892. On the property, they erected a boarding school for black children that was connected to the chapel by a covered walk. By 1894, young SBS were in Saint Catherine Indian School in Santa Fe; in Saint Francis de Sales School in Virginia in 1899; and in 1902 in Saint Michael Indian School on the Navajo Reservation. Gradually, other boarding schools sprang up on reservations. In day schools, the Sisters taught elementary and high school levels in urban and rural areas of the Northeast, the Midwest and the South. In 1917 a school to prepare teachers was established in New Orleans. By 1925 it received a charter as Xavier University of Louisiana.

A severe heart attack in 1935 curtailed Saint Katharine’s missionary travels. Although for about 20 years she lived in prayerful retirement, her love and interest in the missions continued until her death on 3 March 1955. Saint Katharine was the last of the three Drexel sisters to die. The estate of Francis A. Drexel was then distributed to the charities listed in his will. Following the miraculous healing of Robert Gutherman’s eardrum, Saint Katharine was beatified in 1988. The healing of little Amy Wall’s deafness opened the way for her canonization by Pope John Paul II on 1 October 2000.

Today, the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament continue to serve in elementary and secondary schools, as well as at Xavier University of Louisiana in New Orleans, the first Black Catholic university in the United States. They are also involved in a variety of other services including pastoral and spiritual ministries, social services, counseling, religious education, and health care, primarily but not exclusively among Black and Native Americans.

Venerable Cornelia Connelly and Holy Child Shrine

Venerable Cornelia Connelly lived a full and at times very difficult life. She was a wife, a mother, a convert, an educator, and foundress of a religious order. She was born Cornelia Peacock in 1809 in Philadelphia to a large, wealthy Presbyterian family. Her happy childhood didn’t last past her adolescence because she lost both her parents by the time she was 14. She went to live with an older half-sibling, Isabella, who was married but had no children of her own. Cornelia went from living with loving parents and siblings, to living as an only child with caretakers she barely knew. This twist of fate put Cornelia on the winding path that would eventually lead her to England and the founding of the Society of the Holy Child Jesus.

During her time with Isabella and Austin Montgomery, she attended St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church and there met and fell in love with Pierce Connelly, a captivating young preacher. Despite Isabella’s strong objections, the fiercely independent Cornelia followed her heart and married Pierce. Cornelia Peacock was baptized and married, becoming Cornelia Connelly, at the age of 22. Very soon after marrying they moved to Mississippi where Pierce was offered a position as a rector and they had their first child, Mercer. Once again, though, Cornelia’s seemingly stable life was turned on its head.

The young family faced a lot of change in the years ahead thanks primarily to Pierce’s ambitious and restless nature. He wanted to advance his career in his church, but he also grew disillusioned with his Protestant faith. After a missed opportunity to become an Episcopalian bishop, he struck a friendship with a French Catholic. Pierce now desired to be Catholic and to keep his vocation, but Catholic priests were not typically allowed to have families. In Louisiana, Cornelia learned about the Catholic faith on her own and became drawn to it. While the young family waited in New Orleans for their ship to Rome, Cornelia made up her mind to convert to Catholicism while Pierce was weighing his options. She was received into the Catholic Church on 8 December 1835.

The family spent a few years abroad, living off of their investments in the United States. Pierce joined the Catholic Church, more than ever convinced he was being called to the priesthood. When an economic downturn in the U.S. meant the family needed to return home, they moved to Louisiana so Pierce could take a teaching job with the Jesuits. While in Louisiana they suffered two tragic losses. Their infant daughter died at six weeks and their youngest son died as the result of serious burns after being knocked into a vat of boiling sugar. With these losses still fresh, Pierce decided it was time for him to become a priest. He needed Cornelia’s permission and she would have to agree to a life of celibacy. Full of trepidation, but also faith, she agreed to separate from Pierce and accept a life of perpetual chastity. This decision was made official in 1843. They returned to Italy where Cornelia lived in the Sacred Heart convent with her youngest son (born just before Cornelia’s separation from Pierce). But after two years, she decided it wasn’t the life she wanted. She felt called to give her life to God, but not as a cloistered nun. At age 37, with her three remaining children in boarding schools and having been inspired by the Jesuits, she decided to found her own order of religious women, the Society of the Holy Child Jesus. She planned to return to the United States, but the pope urged her to start her order in England. She struggled with the culture and the start of a new order, but was happy and fulfilled and was able to still be a mother to her children and visit them.

Further misfortune awaited Cornelia because Pierce then decided to renounce his priesthood and his Catholic faith. Moreover, he decided to reclaim his wife. He tried everything to pull Cornelia away from her new life, including pulling his children out of school and denying Cornelia rights to visit them. He sued Cornelia claiming she had abandoned him and the children. Connelly versus Connelly went to appeal and was ultimately dismissed, but it did serious damage to Cornelia’s reputation and finances as Pierce refused to pay for the proceedings. He moved to Florence and once again become an Episcopal minister. Cornelia and the Society of the Holy Child Jesus eventually started the American province in Philadelphia where new missions led to its flourishing around the world. Cornelia died at the age of 70 in 1879.

The memorial and shrine were blessed in the Cathedral Basilica on October 17, 2021. Her portrait is painted by the same artist whose earlier version hangs at the mother house in Montgomery County. The eyes and the hands in this version show the weariness of age, but also the peace and joy that was Cornelia’s. The Holy Child Shrine, an image that can be found in most American Holy Child Schools and convents features the gesture of reaching out and stepping forward. The pedestal is adorned with five roses in memory of Cornelia’s five children: Mercer, Ady, John Henry, Mary Magdalene, and Frank.

Most of the local ministries established by the Holy Child Sisters are no longer operative, and those remaining have mostly lay leadership including Rosemont College, Rosemont Holy Child School at Rosemont and Holy Child Academy, Drexel Hill.

[1] The history narrative is largely excerpted with permission from Kishbaugh, Nevin. (2016) America’s Great Cathedrals. Unpublished manuscript.

Self-guided Tour

Click here for a printable PDF of the Basilica’s self-guided tour

Cathedral Audio Tour

An audio tour is available for your MP3 device to assist you on your next visit to the Cathedral Basilica. The tour is approximately twenty minutes in length and the download is free.

Click here to download the Cathedral audio tour file.

Cathedral Photo Tour

Please click on the link below to view a gallery which contains pictures of the beautiful Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul, the Mother Church of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia.

VIEW OUR PHOTO GALLERY